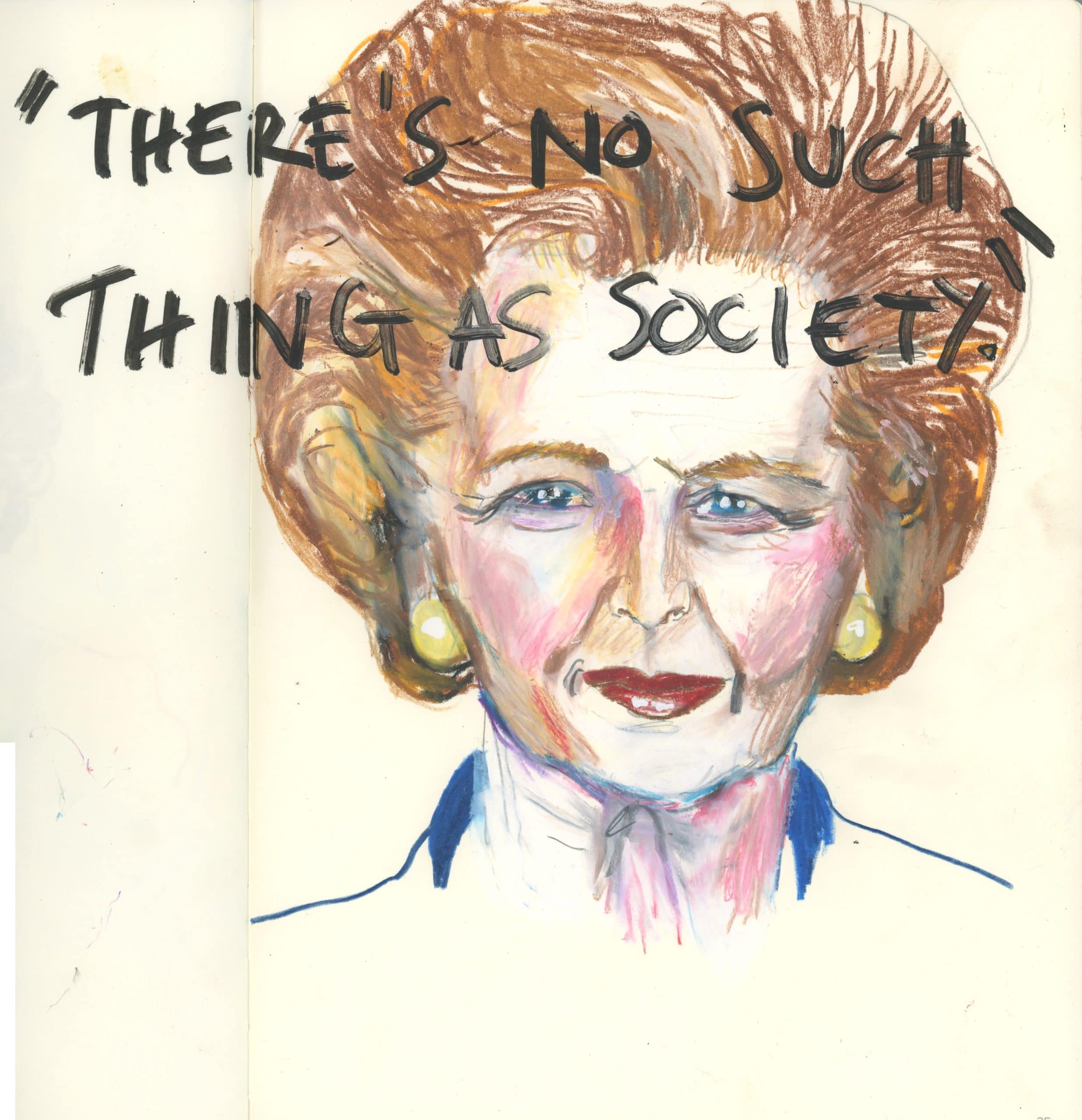

I was driving home from dropping my 10 year old off at school in the rain this morning, when I gave way to a stressed-looking woman, driving a car full of small kids to school. She was clutching the steering wheel like she wanted to wring its neck. I slowed down and I let her across the cross road, and the person behind me blasted the horn, and tried to over-take me on the other side of the road. The lady had already begun to cross, as the coast was supposed to be clear, and so the stress-car had to screech to a halt and just wait on the wrong side of the road. They then tore past at great speed amongst the throngs of school kids and parents and powered off down the street. ‘No such thing as society’ The famous Interview for Woman’s Own Magazine, in which Thatcher expresses this now famous attitude, crossed my mind. Has this quote become entrenched in our societal hive-brain? We are all in our own little bubbles. (Often these bubbles are pretty stressful too.) How can that 1986 interview, when unpacked, be something to be taken seriously? And yet it feels like the bedrock of conservative philosophy. The point of reference which justifies the act of leaving people to suffer. Of choosing not to understand. Of allowing people to go hungry. It happens on both large and small scale.

This is what she said:

“I think we have been through a period when too many people have been given to understand that when they have a problem it is the government’s job to cope with it. ‘I have a problem, I’ll get a grant. I’m homeless, the government must house me.’ They are casting their problems on society. And, you know, there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look to themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then, also, to look after our neighbours. People have got their entitlements too much in mind, without the obligations. There is no such thing as an entitlement, unless someone has first met an obligation.”

Author Samual Brittan writes in the FT about the famous speech. Brittan likens her statement on society to the human body: In short, the notion that a complex whole (the body) only works as a result of individual functioning mechanisms, or cells. Same goes with the cell components..and so on and so forth, right down to sub-atomic particles. Each tiny thing ‘pulls it’s weight. Contributes. And therefore the body works. I see the sense of this idea, but it must surely be clear to any human (with functioning brain cells), that sentient beings cannot be compared to a cell? That’s just ridiculous. I’ll do it now so you can see what I mean: Dave, the malfunctioning cell was physically and mentally abused as a young cell. He didn’t have access to the nutrients he needed to develop properly, and his daddy and mummy cells chipped away at his sense of self-belief. Daddy cell robbed cytoplasm from other cells to make money on the dark cellular web. As a result, Daddy cell was sent to cell prison. Now Dave the damaged cell doesn’t even think he’s a good cell at all, and can’t hold down his job. He can’t even express why because he wasn’t taught to communicate effectively.

That’s silly, isn’t it.

In fact, what the body does, is help to fix damaged stuff all the time. It is this which helps the body to keep functioning effectively and for longer.

It’s all just another example of the human ability to engage in confirmation bias. The author likes the idea of blaming the ‘free loader’. I suspect he has privileges that Dave the dysfunctional cell didn’t have.

When I draw people or write little stories about names on phones, or overheard interactions, my intention is to make them into real people, and possibly to challenge assumptions. If the angry driver I encountered this morning knew or considered the backstories of those who pissed them off (me, and also the woman to whom I gave way), there is no way they would have been that annoyed. Nor would I perhaps, had I known theirs. If the people who write off some parts of our society as ‘freeloaders” knew their backstories, perhaps they would think twice too. Only the likelihood is they’ll never really get it because they’ve never been there, or perhaps just because they can’t accept that success might also have involved luck.

Sometimes the people we consider, and certainly the people I draw, are more loveable, and sometimes less so, but what I would love to happen is that it makes people who read it just give a moment to be more forgiving. And possibly, if they have a moment, to help.